Dogs have been working with people for centuries. Think hunting dogs, herding dogs, police dogs or search and rescue dogs. But have you heard of conservation dogs?

Conservation dogs fall mainly into two categories: guardian dogs and sniffer dogs (also called scent, detection or detector dogs).

Guardian dogs protect vulnerable species from predators, while sniffer dogs locate targets of interest using their powerful sense of smell.

In the past 15 years, dogs have begun to play a crucial role in conservation around the world. So let’s take a closer look at them, with a focus on their work in Australia.

The nose that knows

Guardian dogs were made famous by the 2015 movie Oddball. The film is based on the true story of Maremma dogs, trained to protect little penguins from foxes on Middle Island near Warrnambool in southwest Victoria. The penguin population had dwindled to fewer than ten before the Maremma dogs got involved. The breed was chosen for its long association with guarding sheep in Europe.

But most conservation dogs are sniffer dogs, because there are so many uses for them. They can be trained to find animals or plants, or “indirect” signs animals have left behind such as poo or feathers.

Dogs can detect anything with an odour – and everything has an odour. Sniffer dogs are trained to detect a target scent and point it out to their human coworker (sometimes referred to as handler or bounder).

Sniffer dogs have been trained for various missions such as:

-

finding rare and endangered species

-

detecting invasive animals during eradication or containment such as fire ants or snakes

-

locating pest plants

-

supporting wildlife surveys by detecting scats (poo), urine, vomit, nests, carcasses and even diseases.

They have worked in extreme conditions on land (including on sub-Antarctic islands) and at sea, and can even detect scent located underground. Sniffer dogs have also trained to recognise individual animals such as tigers by scent.

The ultimate scent detection machine

A dog’s nose is estimated to be 100,000 to 100 million times more sensitive than a human nose (depending on the dog breed). A much larger proportion (seven to 40 times larger) of the dog’s brain is dedicated to decoding scent.

That means dogs can detect very low scent concentrations – the equivalent of a teaspoon of sugar in five million litres of water (or two Olympic-sized swimming pools). They can also differentiate between very similar odours.

Dogs analyse the air from each of their nostrils independently, detecting tiny variations in scent concentration. This gives them a directional sense of smell that can guide them left or right until they’ve honed in on the origin of the scent.

Thanks to very sophisticated nostrils, dogs can avoid contaminating an odour with their own breath (exhaling air through the nostrils’ sides). They also can analyse odours continuously regardless of whether they are inhaling or exhaling.

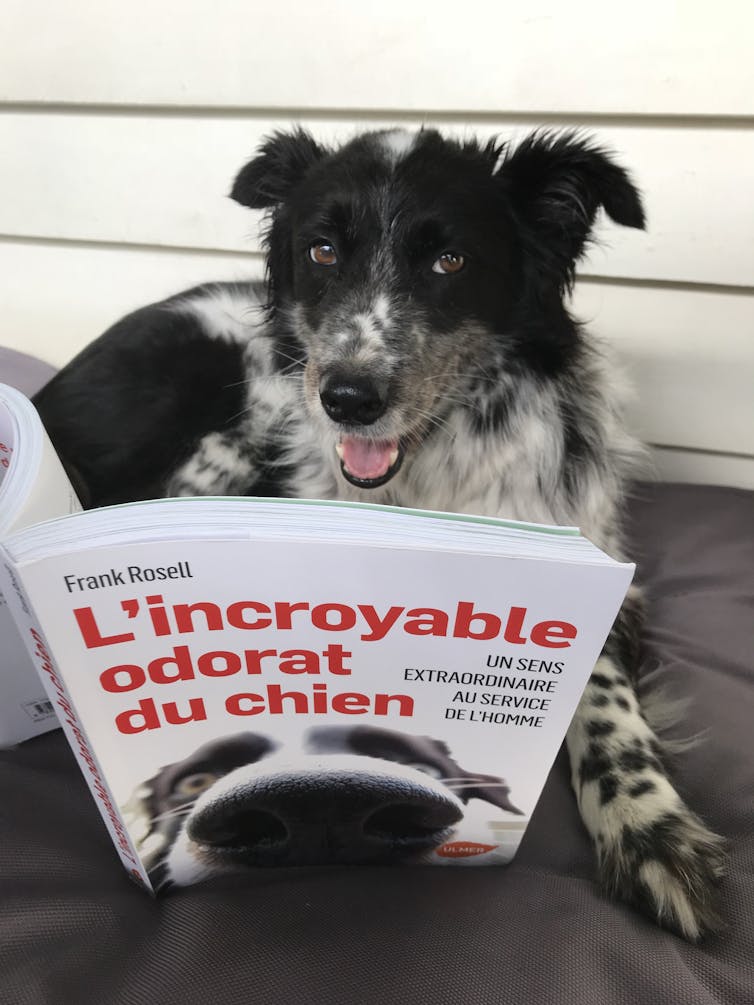

Besides being the ultimate scent detection machine, dogs are great ambassadors for conservation – melting hearts all the way to Hollywood.